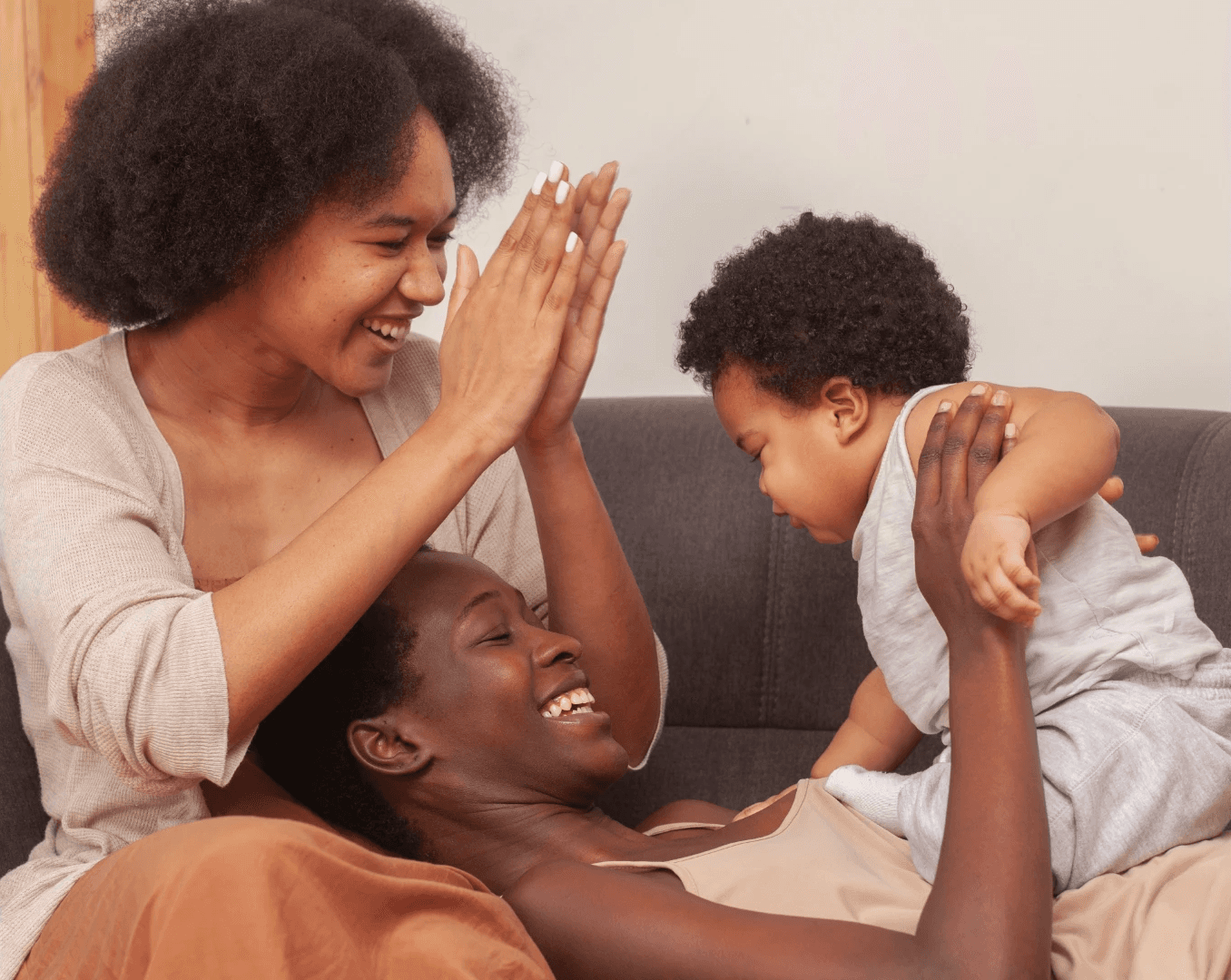

August 1st marked Emancipation Day across much of the English-speaking Caribbean, and in the West Indian diaspora here in Canada.

When all enslaved Black people were finally, legally, freed from bondage in 1838, it marked a new dawn for many of our ancestors. Though limited, they would have rights and freedoms not previously accessible to them.

Over the span of the next century, several islands gained their independence from British rule. In Jamaica, August 6, 1962, marked Independence Day. The week of August 1st to August 6th is celebrated as ‘Emancipendence Week,’ with festivities that shut down the island the first week of August.

The first Caribbean country to celebrate Emancipation Day as a public holiday was Trinidad and Tobago in 1985.

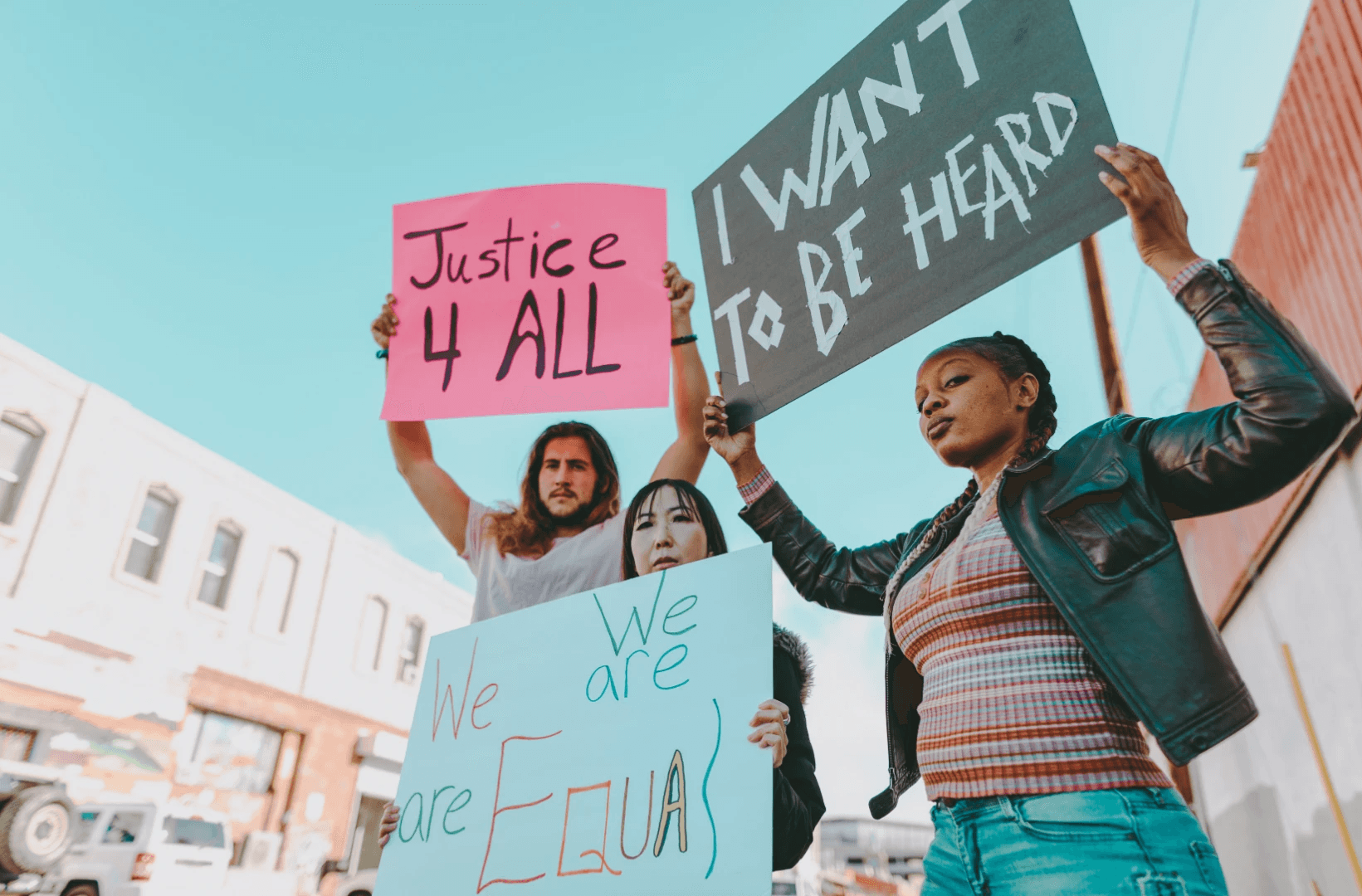

And as celebrations revved up across the Caribbean this year, news out of Saint Lucia was more exciting than any fireworks display. The island had overturned colonial era anti-gay sex laws.

On July 29th, mere days before Emancipation Day, a High Court judge ruled that ‘buggery’ laws were unconstitutional. It is an exciting, growing trend across the Caribbean. The ruling in Saint Lucia follows other island nations, such as Barbados, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Dominica, and Antigua and Barbuda, in striking down similar repressive and homophobic laws.

What does this have to do with Emancipation Day?

Walk with me.

The original Emancipation Day released our ancestors from legal bondage and slavery.

And in many Caribbean countries, ancient laws around ‘buggery’ and queerness are still very much on the books.

It begs the question, what does emancipation mean to the queer West Indian?

Ide Thompson, a Black and queer academic from Nassau, Bahamas, says that there’s a ‘clear need’ for queer emancipation.

“When it comes to our consciousness and trying to fight for rights, freedoms, and acceptance, I think Emancipation Day feels like a slap in the face. Because you can celebrate freedom but there’s inequality under the law in the Bahamas when it comes to queer relations,” Thompson said. “Emancipation Day for us in the queer community back home is a time of like, thinking

‘Okay, what can we do to really help push the movement forward?’ What does it mean to…have people in the Bahamas to say, ‘Queer people have been here this whole time.’”

He recalled reading ‘The Long Emancipation: Moving Toward Black Freedom’ by Rinaldo Walcott, and how Walcott defines what emancipation really is.

“He's making this argument that emancipation isn't an event, but a process, and that all of us in African majority countries or anyone who has been colonized, it's still this process of finding emancipation,” he explained. “Because even if we were given it and we’re independent, we're still very much controlled by external forces or internal forces in league with external forces. Or we're still culturally and socially interacting in colonial ideologies and thought patterns and ways of socializing ourselves. Even queerness is, in a lot of ways, impacted by these forces.”

The forces in question come from the legacy of colonialism in the Caribbean. Many of the homophobic laws in the English speaking Caribbean come from the colonial era.

In both Jamaica and the Bahamas, ‘buggery’ (anal sexual intercourse) laws came directly from the ‘Offences Against the Person Act’ of 1861. The law was put in place by the Parliament of the United Kingdom, the rulers of both nations. Section 61 and 62 of the law proclaimed that buggery would no longer be punishable by death, but instead a lifetime imprisonment. Those laws came from the ‘Buggery Act’ of 1533, passed by Henry VIII, long before the ‘discovery’ of the Caribbean by colonizers. In the United Kingdom, the laws against buggery were repealed in England and Wales in 1967. They remain on the books for many Caribbean countries today.

Same-sex activity is legal in the Bahamas, but like many Caribbean nations, there are no legal protections for harassment and discrimination towards gender, sexual orientation, or legal recognition for queer relationships.

Thompson recalled being chased by high schoolers who threw stones and bottles at him on his way to university. And then, he’d go on to receive discrimination from other students and or faculty at the school.

“Even being a college student at the University of the Bahamas, I have experienced firsthand discrimination.The charter of the University, when it was founded in 2016, has sexual orientation and gender expression as protected classes. Yet, there's no way to report or address these issues. All the queer people on campus were experiencing similar things,” he explained.

With that being said, it isn’t all doom and gloom for queer West Indians. There are gatherings like the Caribbean Women and Sexual Diversity Conference coming up in St. Kitts and Nevis this October. In Jamaica, an actual lesbian commune called ‘Kindred on the Rock’ was founded and is run by renown lesbian poet Staceyann Chin. And organizations like SASOD Guyana have been around since 2003, winning awards for changemaking for queer Guyanese people. All across the Caribbean, there is work resisting colonial era laws and mentalities. It is an uphill battle, and no one is coming to save West Indians. We have to do the work ourselves.

“We feel like we have to go away to be free. We run away to another country. ‘If I go to America, if I go to Canada, if I go to Europe.’ Nobody told me I could be whatever I want. I think when we finally realize if we can get to go back home and be who we want, that's when you're really finally free.”